Hidden in Plain Sight

In 1964, civil rights workers James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner went missing in Mississippi during the Freedom Summer voter registration drive, shortly after being released from a Philadelphia, Mississippi, jail where they had been taken to pay a speeding fine. President Lyndon Johnson ordered FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover to send FBI agents to find them. Searchers found the bodies of eight black men, including two college students who were working on the voter registration drive, before an informant’s tip finally led the agents to an earthen dam where Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner were buried. After local law enforcement refused to investigate the murders, the Justice Department charged 19 Ku Klux Klansmen with conspiring to violate Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner’s civil rights. Two current and two former law enforcement officials were among those charged. An all-white jury convicted seven of the Klansman but only one of the law enforcement officers.

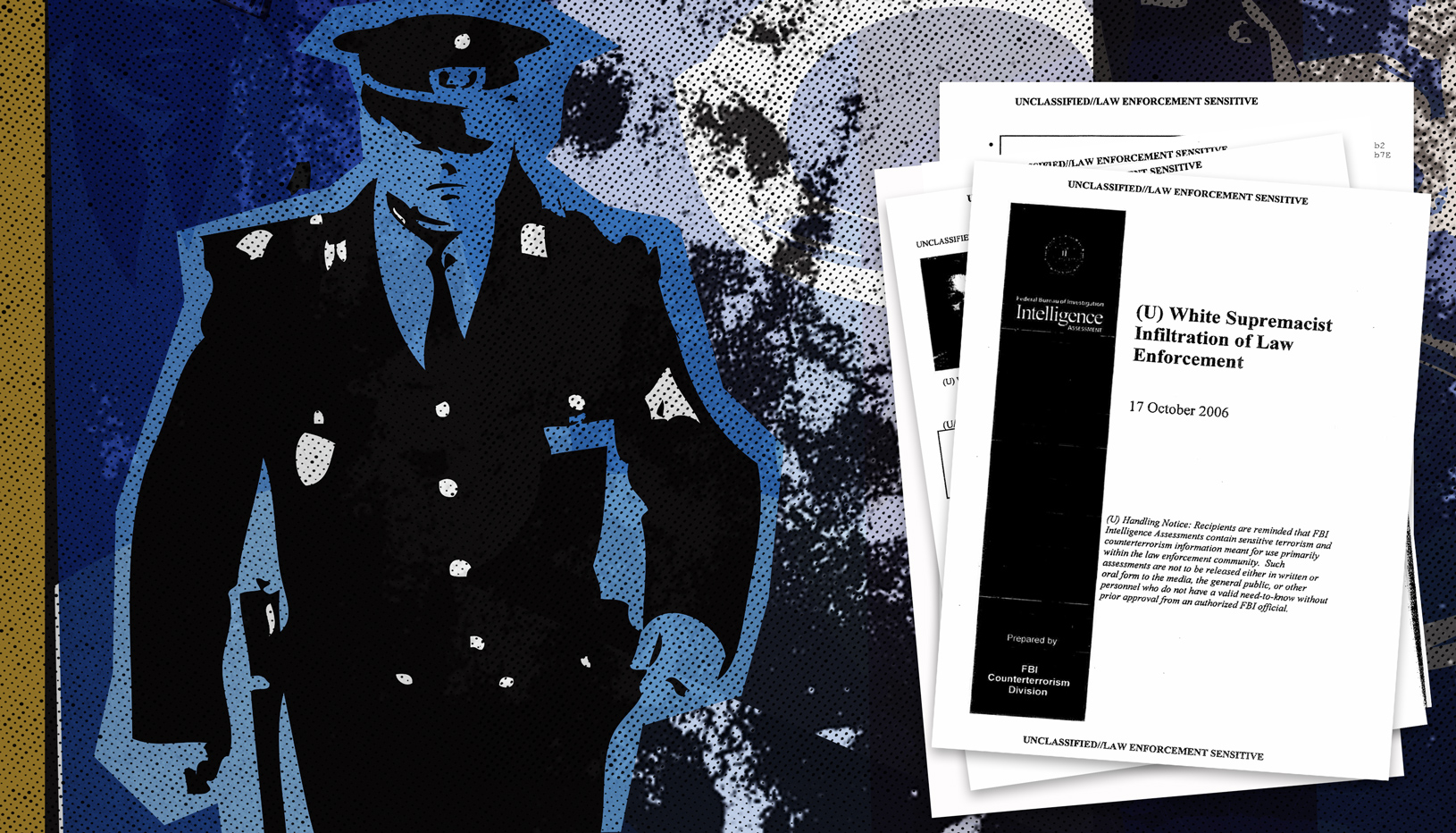

While the Mississippi Burning case was the most notorious, it was far from the last time white supremacist law enforcement officers engaged in racist violence. There is an unbroken chain of law enforcement involvement in violent, organized racist activity right up to the present. In the 1980s, the investigation of a KKK firebombing of a Black family’s home in Kentucky exposed a Jefferson County police officer as a Klan leader. In a deposition, the officer admitted that he directed a 40-member Klan subgroup called the Confederate Officers Patriot Squad (COPS), half of whom were police officers. He added that his involvement in the KKK was known to his police department and tolerated so long as he didn’t publicize it.

In the 1990s, Lynwood, California, residents filed a class action civil rights lawsuit alleging that a gang of racist Los Angeles County sheriff’s deputies known as the Lynwood Vikings perpetrated “systematic acts of shooting, killing, brutality, terrorism, house-trashing and other acts of lawlessness and wanton abuse of power.” A federal judge overseeing the case labeled the Vikings “a neo-Nazi, white supremacist gang” within the sheriff’s department that engaged in racially motivated violence and intimidation against the Black and Latino communities. In 1996, the county paid $9 million in settlements.

Recent reporting suggests this overtly racist gang activity within the sheriff’s department continues. In 2019, Los Angeles County paid $7 million to settle a wrongful death lawsuit against two sheriff’s deputies for shooting an unarmed Black man after testimony revealed that they were part of a group of deputies with matching tattoos in the tradition of earlier deputy gangs. A pending lawsuit accuses the same two officers of beating an unarmed Black man while yelling racial epithets. A Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors investigation revealed that almost 60 lawsuits against alleged members of deputy gangs have cost the county about $55 million, which includes $21 million in cases over the last 10 years. These deputy gangs pose a threat to their fellow law enforcement officers as well, according to two recently filed lawsuits. In one, a deputy alleges he had been bullied by deputy gang members for five years, and finally viciously beaten by the gang’s enforcer. In another, a deputy who witnessed the attack alleged he suffered threats and retaliation from deputy gang members after reporting it to an internal affairs tip line. In 2019, the FBI reportedly initiated a civil rights investigation regarding gang activity at the sheriff’s department.

Only rarely do these cases lead to criminal charges. In 2017, Florida state prosecutors convicted three prison guards of plotting with fellow KKK members to murder an inmate. Federal prosecutions are even rarer. In 2019, the Justice Department charged a New Jersey police chief with a hate crime for assaulting a Black teenager during a trespassing arrest after several of his deputies recorded his numerous racist rants. This incident marked the first time in more than a decade that federal prosecutors charged a law enforcement official for an on-duty use of force as a hate crime. A jury convicted the police chief of lying to FBI agents but was unable to reach a verdict on the hate crime charge, which prosecutors vowed to retry.

More often, police officers with ties to white supremacist groups or overt racist behavior are subjected to internal disciplinary procedures rather than prosecution. In 2001, two Texas sheriff’s deputies were fired after they exposed their KKK affiliation in an attempt to recruit other officers. In 2005, an internal investigation revealed a Nebraska state trooper was participating in a members-only KKK chat room. He was fired in 2006 but won his job back in an arbitration mandated by the state’s collective bargaining agreement. On appeal, the Nebraska Supreme Court upheld his dismissal, determining that the arbitration decision violated “the explicit, well-defined, and dominant public policy that laws should be enforced without racial or religious discrimination, and the public should reasonably perceive this to be so.” Three police officers in Fruitland Park, Florida, were fired or chose to resign over a five-year period from 2009 to 2014 after their Klan membership was discovered. In 2015, a Louisiana police officer was fired after a photograph surfaced showing him giving a Nazi salute at a Klan rally.

In 2019, a police officer in Muskegon, Michigan, was fired after prospective homebuyers reported prominently displayed Confederate flags and a framed KKK application in his home. The police department conducted an investigation into potential bias, examining the officer’s traffic citation rate and reviewing an earlier internal affairs investigation into an excessive force complaint and two previous on-duty shootings, each of which were found justified. (The investigation uncovered a third, previously unreported shooting in another jurisdiction that was not further described). Although the internal investigation documented the officer citing Black drivers at a higher rate than the demographic population in the district he patrolled, it determined that the officer was not a member of the KKK and had shown no racial bias on the job. Still, the report concluded that the community had lost faith in the officer as a result of the incident, and the police department fired him. The officer settled a grievance he filed with the Police Officers Labor Council regarding his termination, agreeing to retire in exchange for his full pension and health insurance.

In June 2020, three Wilmington, North Carolina, police officers were fired when a routine audit of car camera recordings uncovered conversations in which the officers used racial epithets, criticized a magistrate and the police chief in frankly racist terms, and talked about shooting Black people, including a Black police officer. One officer said that he could not wait for a declaration of martial law so they could go out and “slaughter” Black people. He also announced his intent to buy an assault rifle in preparation for a civil war that would “wipe ’em off the [expletive] map.” The officers confirmed making the statements on the recording, but they claimed that they were not racist and were simply reacting to the stress of policing the protests following the killing of George Floyd. In addition to the officers’ dismissal, the police chief ordered his department to confer with the district attorney to review cases in which the officers appeared as witnesses for evidence of bias against offenders.

In July 2020, four police officers in San Jose, California, were suspended pending investigation into their participation in a Facebook group that regularly posted racist and anti-Muslim content. In a post about the Black Lives Matter protests, one officer reportedly responded, “Black lives really don’t matter.” In a positive development, the San Jose Police Officers’ Association president vowed to withhold the union’s legal and financial support from any officer charged with wrongdoing in the matter, stating that “there is zero room in our department or our profession for racists, bigots or those that enable them.”

In some cases, law enforcement officials who detect white supremacist activity in their ranks take no action unless the matter becomes a public scandal. For example, in Anniston, Alabama, city officials learned in 2009 of a police officer’s membership in the League of the South, a white supremacist secessionist group. The police chief, however, determined that the officer’s membership in the group did not affect his performance and allowed him to remain on the job. In the following years the officer was promoted to sergeant and eventually lieutenant. It wasn’t until 2015, after the Southern Poverty Law Center published an article about a speech he had given at a League of the South conference in which he discussed his recruiting efforts among other law enforcement officers, that the police department fired him. A second Anniston police lieutenant found to have attended the same League of the South rally was permitted to retire. The fired officer appealed his dismissal. After a three-day hearing, a local civil service board upheld his removal. The officer then filed a lawsuit alleging that his firing violated his First Amendment free speech and association rights, but a federal court affirmed the termination.

The Anniston example demonstrates the need for transparency, public accountability, and compliance with due process to successfully resolve these cases. The Anniston Police Department and city officials knew about these officers’ problematic involvement in a racist organization for years, but it took public pressure to finally compel action. They then responded correctly, in awareness of the public scrutiny, by dismissing the officer in a manner that provided the due process necessary to withstand judicial review. The department then implemented a policy requiring police officers to sign a statement affirming that they are not members of “a group that will cause embarrassment to the City of Anniston or the Anniston police department.” It requested conflict resolution training from the DOJ Community Relations Service. These were positive steps to begin rebuilding public trust. But as in many of these cases, during the nine years when avowed white supremacist police officers served in the Anniston Police Department (including in leadership positions), there was not a full evaluation or public accounting of their activities. The Alabama NAACP requested that the DOJ and U.S. attorney examine the officers’ previous cases for potential civil rights violations, but there is no evidence that either ever initiated such an investigation. This decision forfeited another opportunity to restore public confidence in law enforcement.

Unfortunately, there is no central database that lists law enforcement officers fired for misconduct. As a result, some police officers dismissed for involvement in racist activity are able to secure other law enforcement jobs. In 2017, the police chief in Colbert, Oklahoma, resigned after local media reported his decades-long involvement with neo-Nazi skinhead groups and his ownership of neo-Nazi websites. A neighboring Oklahoma police department hired him the following year, claiming he had renounced his previous racist activities and held a clean record as a police officer.

In 2018, the Greensboro, Maryland, police chief was charged with falsifying records to hire a police officer who had previously been forced to resign from the Dover, Delaware, police department after he kicked a Black man in the face and broke his jaw. The same officer was later involved in the death of an unarmed Black teenager, which sparked an investigation that revealed 29 use of force reports at his previous job, including some that found he used unnecessary force. The previous incidents were never reported to the Maryland police certification board.

Prosecutors have an important role in protecting the integrity of the criminal justice system from the potential misconduct of explicitly racist officers. The landmark 1963 Supreme Court ruling in Brady v. Maryland requires prosecutors and the police to provide criminal defendants with all exculpatory evidence in their possession. A later decision in Giglio v. United States expanded this requirement to include the disclosure of evidence that may impeach a government witness. Prosecutors keep a register of law enforcement officers whose previous misconduct could reasonably undermine the reliability of their testimony and therefore would need to be disclosed to defense attorneys. This register is often referred to as a “Brady list” or “no call list.”

Georgetown Law Professor Vida B. Johnson has argued that evidence of a law enforcement officer’s explicitly racist behavior could reasonably be expected to impeach his or her testimony. Prosecutors, therefore, should be required to include these officers on Brady lists to ensure defendants they testify against have access to the potentially exculpating evidence of their explicitly racist behavior. This reform would be an important measure in blunting the impact of racist police officers on the criminal justice system. In 2019, progressive St. Louis prosecutor Kimberly Gardner placed all 22 of the St. Louis police officers that the Plain View Project identified as posting racist content on Facebook on her office’s no call list.

"right" - Google News

August 27, 2020 at 09:12PM

https://ift.tt/2QwSMnL

Hidden in Plain Sight: Racism, White Supremacy, and Far-Right Militancy in Law Enforcement - brennancenter.org

"right" - Google News

https://ift.tt/32Okh02

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Hidden in Plain Sight: Racism, White Supremacy, and Far-Right Militancy in Law Enforcement - brennancenter.org"

Post a Comment