Four years later, things have changed. Rather than speaking at the RNC, Falwell was instead in the midst of an epic fall from grace -- leaving many Christian conservatives to wonder how the namesake of the Moral Majority founder ended up battling allegations of a sexual affair, needing help from Trump's disgraced fixer, and forced to resign from the university he built into one of the most financially successful Christian schools in the country.

On Monday, the first day of the GOP convention, Falwell announced his intention to resign from Liberty following allegations from a former hotel pool attendant who claims to have had a sexual relationship with Falwell and his wife, on the heels of a controversy about a photo he appeared in that violated Liberty's own moral code.

His fall potentially marks the end of the Falwell family's prominent role as evangelical political powerbrokers. It also bookends a story that began more than 40 years ago when Falwell's father, televangelist Jerry Falwell Sr., founded the Moral Majority and began to aggressively organize conservative Christians as a political constituency. The elder Falwell permanently lodged social conservatives and White evangelicals into the GOP coalition to ensure that no Republican could win without their support.

After Falwell Sr. died in 2007, Falwell took on his father's mantle, growing the financially troubled Liberty into a Christian behemoth with an endowment worth more than $1 billion. He also became a gatekeeper for Republican politicians seeking entry into the conservative evangelical world.

But the shine wore off as scrutiny of both Falwell's business practices and his personal life left him ever more isolated in the evangelical world -- and now, politically diminished for Trump, who no longer needs validation within the evangelical community. In the transactional world of politics, Falwell served his purpose for Trump by giving him credibility among the faithful -- a particularly valuable commodity amid the subsequent flurry of headlines about paying for a porn star's silence and the Access Hollywood tape. Though Falwell's sins are entirely his own, he is hardly the first, and likely not the last, to exit his relationship with Trump deeply diminished.

For some conservative evangelicals, Falwell's demise offers an opportunity to dispense with the idea that he was ever truly representative of Christian political interests -- and to take measure of an era where the religious right found itself aligned with an administration that, in the minds of many, had lost its claim to any moral high ground with policies that placed immigrant children behind bars and rhetoric that targeted religious minorities.

"Donald Trump doesn't understand us," said Hunter Baker, a professor and dean at the evangelical Union University in Jackson, Tennessee. "Falwell is the perfect kind of person to fill that role because it's a power equation. I think that Trump understands power."

The rise of the Falwells and the religious right

Falwell's story parallels the evolution of conservative Christian political players over the past two generations -- from recognizing the untapped opportunity of Christian voters to playing a powerful part of the GOP coalition.

More than anyone, Jerry Falwell Sr. can claim responsibility for bringing conservative Christians into the Republican fold. Politically homeless in the 1970s, evangelicals and social conservatives organized under Falwell's Moral Majority. The broad religious right was a critical part of Ronald Reagan's "three-legged stool" that also included anti-Communist hawks and fiscal conservatives.

That place in the GOP coalition strengthened over the next few decades, with Republicans delivering on agenda items like conservative judges, restrictions on abortion and defense of religious institutions.

But social conservatives and evangelical leaders maintained a conditional relationship with the Republican Party. At a closed-door meeting in 1998, the New York Times reported at the time, Focus On the Family founder James Dobson told his fellow social conservatives that if the GOP continued to "betray" evangelical voters on social issues like homosexuality and sex education funding that he would leave the party and "do everything I can to take as many people with me as possible."

This sort of credible threat demonstrated the position evangelicals found themselves in the world that Falwell Sr. built: dictating the terms to a party that needed their votes. By the time Falwell Sr. died in 2007, a self-proclaimed born-again Christian named George W. Bush was the Republican president and evangelicals were increasingly ensconced in the party's power structure.

So when Falwell Jr. took over Liberty University, he was inheriting a keen sense of the political power that came with it. A lawyer and college administrator but not a minister like his father, Falwell Jr., is not a liturgical leader among evangelicals. But his growth of Liberty from a small, perpetually cash-strapped Christian school to an evangelical powerhouse with a $1.6 billion endowment and more than 100,000 students (the majority of them online) elevated him as both a gatekeeper and a success story that was attractive to Republican politicians.

It was no coincidence that evangelical favorite Ted Cruz launched his candidacy for president in 2015 onstage at Liberty's convocation, a regular gathering of all students for prayer and fellowship. And it shocked and resonated when, just before the 2016 Iowa caucuses, Falwell gave his endorsement not to Cruz -- the social conservative champion -- but to Trump.

It also raised questions about the political goals of evangelical Christians. While some of the agenda items have shifted since the Reagan administration, the religious right has also advocated for higher moral character among elected officials. Falwell made little effort to claim that about Trump, a thrice-married former casino owner who had demonstrated little public interest in the spiritual life. Falwell embraced Trump for reasons that went beyond his Christian identity, praising Trump's business know-how and called him a "a wonderful father and a man who I believe can lead our country to greatness again."

But there were also some unusual circumstances adjacent to Falwell's endorsement. In 2015, months before he backed Trump, Falwell spoke with Trump lawyer and fixer Michael Cohen about helping keep some racy "personal" photographs from becoming public, Cohen confirmed to CNN this week. And before Trump began his run for the presidency in 2015, Cohen hired a Liberty University employee, John Gauger, to rig online polls in Trump's favor, the Wall Street Journal reported in 2019.

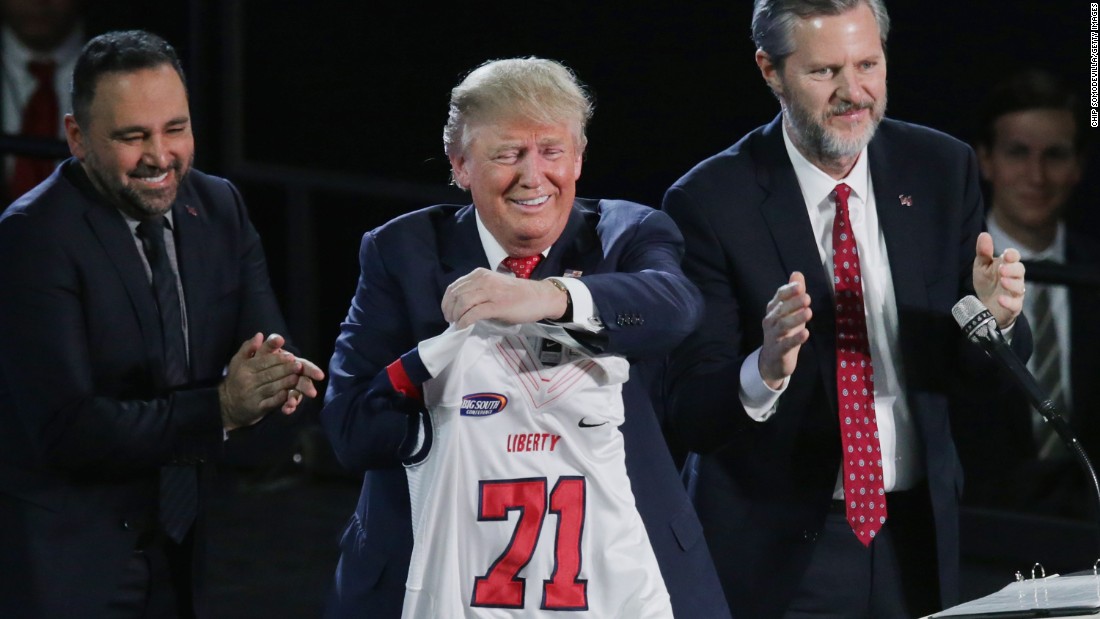

Whatever the reason, the endorsement was mutually beneficial, giving Trump cachet with evangelical Christian voters and Falwell access to power. His association with Trump for the past four years has boosted his own profile and that of Liberty University, where Trump delivered the commencement address in 2017.

Meanwhile, Falwell has joined the rotating cast of unofficial outside advisers to the President and has been a regular visitor to the White House, including on Election Night in 2018. His wife Beckie Falwell is on the advisory board for Women for Trump. Together, the Falwells have been the face of politically engaged evangelicalism in the Trump era, making Falwell Jr.'s downfall all the more damaging to conservative Christians.

Costi Hinn, a prominent evangelical pastor in Arizona, said it has been "problematic" to have Falwell represent evangelicals on the political stage, calling him a "wolf in sheep's clothing."

"For evangelicals, the question is, are the people representing us in the White House of character?" Hinn said. "These are the days where we all miss Billy Graham, because he had integrity. He had character."

(Graham's granddaughter, Cissie Graham Lynch, spoke Tuesday at the RNC.)

What's next for evangelicals?

The question for evangelicals concerned both about their position in politics and the future of Christian higher education is: What happens next?

The close association of Liberty with Trump, and Falwell's deeper dive into partisan politics, has rankled several alumni and faculty, some of whom have left the university over it.

The growth of the school has also come with criticisms of Liberty's aggressive approach and how the school is spending its resources. Taking advantage of the explosion in online, for-profit higher education, Liberty boasts an online student body of more than 100,000. That influx of cash has helped the university expand its physical campus in Lynchburg -- benefiting the much smaller 19,000 residential students the school claims.

That strategy raises questions, too, about the ethics of Liberty using its non-profit-status to accept federal loans from its online students, only to leave those students with the obligation to pay off the loans. Under Trump and Education Secretary Betsy DeVos, federal rules policing for-profit universities have been relaxed.

All of it worries others in the field of Christian higher education, who say Falwell's partisan activities and Liberty's assertive business model could paint Christian colleges in a bad light.

"We would not want to paint a target on our back by getting more involved in retail politics," said Baker. "I think [Falwell] caused Liberty to fly too close to the sun."

"right" - Google News

August 29, 2020 at 09:01PM

https://ift.tt/3gH2U8j

As Trump seeks reelection, a chapter closes on the religious right's Falwell era - CNN

"right" - Google News

https://ift.tt/32Okh02

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "As Trump seeks reelection, a chapter closes on the religious right's Falwell era - CNN"

Post a Comment